- Home

- Donna Mabry

Maude Page 9

Maude Read online

Page 9

“I nodded and smiled to myself as if I found my sister’s meanness to be funny, but I didn’t argue with her. It doesn’t do to cross her when she’s like that. Bessie glared at me awhile and, satisfied I’d follow her orders, sat at her place at the table and held out her hands on each side, calm as anything. ‘Now, let’s sit down and give thanks for this meal.”

“John ate with his face down, like he was afraid to speak. After we were through, he and I went outside for a smoke while Bessie cleaned up the kitchen.

“John cleared his throat, like he was halfway afraid to bring up the subject. ‘George, are you really going to marry Maude?”

“I have to. You heard what Bessie said.”

“Well, yes, but you’re not afraid of Bessie, are you, George? She loves you. She wouldn’t really hurt you. She couldn’t anyway. She’s only a woman.”

“I looked at John for a minute and asked, ‘You two never had a bad fight?’

He shrugged. “We argue about this and that, just like any married folk do.”

“Well, if you ever see that look on her face she had tonight, don’t argue, just do what she says.”

“But, like I said, she’s only a woman, and either one of us could knock her down without even working hard at it.”

“I don’t believe in a man hitting a woman, no matter what she does, and besides, she’s not a regular woman, John. There are times she’s going to be just like our mother. You’ll live happier if you know when that is.”

John laughed at me. “Come on, how bad could they be?”

“Bad enough that I’m going to saddle up in the morning and ask Maude to marry me. I been thinking about it anyway. I like her. She’s got a way about her.”

“Bessie behaves just like your mother, you say?”

“Almost, but not as mean.”

“How did your father put up with it? Didn’t he ever do anything to stop her? I don’t think I would tolerate it if she hit me like she did you.”

“Dad was afraid of her, just like I am.”

“Right up until he passed away?”

“I guess so.”

“Guess so?”

“We don’t know for sure what become of him. One day, about ten years ago, he was there in the evening when we went to bed, and the next day he was gone.”

“I’m not surprised. He probably ran off so he wouldn’t have to live with her anymore.”

“Maybe so, but he didn’t take any of his clothes, and he didn’t take his horse.”

After telling me this, George threw back his head and laughed. He said, “We both know for a fact, John never looked at Bessie in the same way again. As long as they lived together, they got along just fine.”

Chapter 12

The next day, it was around nine in the morning when George rode up. When I saw him, I felt like one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse had come to call. He tied Pawnee to the post and knocked on the cabin door. I came out to meet him, with no smile and nothing to say.

He said it right out. “Maude, I want you to be my wife.”

I felt like I was falling in a deep pit and there wasn’t one thing I could do to stop it. I looked away and nodded. He leaned over and kissed me on my cheek. I didn’t tilt it up to make it easier for him. He said, “I know how you like your church, so if we can get the preacher to say the vows tomorrow morning, I’d like to get an early start home. I’m late for my job already, or I’d stay a few days longer. John brought my wagon here when he came home with Bessie, so we can take it back to Missouri and carry what you want with us.”

I looked up at him. “I was wondering if you would think about staying here to live, George. You’d be close to Bessie, and Lulu wouldn’t have to leave her friends. Mom Connor said we could stay in the cabin as long as we wanted.”

“That’s right nice of her, Maude, but I got a good job at home. I got a house to take care of, and livestock, and I have to see after my mother.”

It hurt my heart to hear that, but what could I say? I nodded. “I’ll talk to the preacher about tomorrow. I have a lot to do today. I’ll meet you at the church in the morning. Ten o’clock ought to be all right.”

I stood for a minute on the porch after he left. When I turned around, Lulu was standing inside the door, tears streaming down her face. I could feel my heart breaking for both of us. I sat on the rocker and pulled Lulu on my lap. I held and rocked her for a long time. From time to time, I cried some, too.

I went to the parsonage and told Sister and Brother Clark and he said he could perform the ceremony the next morning. I cried on my way home. Having the time set made it real to me. I went back to my cabin to get ready to move to Missouri. While we packed, Lulu sobbed off and on the whole afternoon. We both wiped away tears as we folded our things.

I looked over my few dresses, thinking about what I should wear for my wedding the next day. I ran my fingertips over the dress with the embroidered white flowers that I made for my wedding to James and laid it out on the bed. There was no way I could bring myself to wear that. It would be like committing adultery on James.

I took James’s plaid shirt I’d worn the day he died. I hadn’t washed it since. I held it up to my face and breathed in deep, hoping to catch a trace of his scent, but it had faded away. Then I folded it up inside the wedding dress and packed them in the cedar chest Tommy made me. They were the only parts left of the dream James and I had lived. I finally chose an everyday blue calico dress that I’d worn many times for my second wedding.

I told Mom Connor about the wedding, and I suppose Lulu told her friends. The Clarks might have mentioned it to someone, and maybe Bessie said something to a neighbor. The next day, there wasn’t an empty pew in the Holiness Church when the preacher gave George and me our vows. The gossipy women of the town came early and sat right down front to make sure George did the right thing. Even some of the Baptists came to see.

The preacher used the opportunity to preach to all the married couples in the church without the usual sermon, just by reading the Bible. I’d taken him aside and asked him to leave out the passage from Ruth that I’d memorized for my wedding to James, so he quoted from Ephesians 5, 22-33, about how husbands and wives are supposed to act toward one another.

I did agree to love, honor and obey. George promised the usual. I took my vows in my church in front of God and we were man and wife. It was done and done, no going back, ever. As we left the church, the preacher handed me an envelope. “Here are the letters of membership for you and Lulu to give to your new church. We’re going to miss you, Maude.”

We had a quick meal with Mom Connor and Helen’s family at Mom’s house, and George loaded Lulu’s and my clothes and personal things on the wagon. There wasn’t much room for anything else. George told me his house was completely furnished, so I left behind all the furniture except the little cradle James made for Lulu. I expected I might need it again. I hoped George would be the tender lover James had been.

After hugs all around and promises from Helen and Bessie that Kennett was only a few miles away from home and they would visit back and forth every chance they got, George helped Lulu and me up on the wagon seat. Mom Connor handed us a picnic basket she’d filled for our dinner.

As we drove away, I looked back and gave a little wave to my family. All the girls and women cried. I wrapped my arm around Lulu’s shoulders and patted her back. Lulu’s tears let up a little, and after a few hours on the road, she fell asleep leaning against my side.

The only life I’d ever known faded in the background, and I steeled myself to face my future. I’d have to find my way in a strange place, with only Lulu, my few belongings, and the stranger who sat next to me on the wagon seat.

Chapter 13

It was late afternoon when we stopped on the banks of the Mississippi to spend the night across the river from Caruthersville, Missouri. We could see the Powell Ferry on the other side. It would take us across in the morning. I’d lived all my life only a few miles f

rom the river, but had never seen it before. It was a wonderful and frightening thing to me. I learned in school that it stretched all the way to the south end of the United States. I watched the boats with their cargo pass by and thought about the places they would stop before they found New Orleans. I daydreamed a little about what it would be like to get on one of the boats with Lulu and sail away from the life that faced me.

We ate our dinner from the picnic basket and rested for a while. George unhitched Pawnee to let him drink from the stream and nibble at the long grass.

“Aren’t you going to hobble him?” I asked.

“I don’t have to hobble him. He always stays within forty or fifty feet of me. I brought him into the world. I raised him as much as his mother did. When he was only a few hours old I started handling him and brushing him every day. I put a halter on him right off and trained him gentle. I had him following a lead when he was still a baby.”

“How many horses do you have?” I asked.

“He’s the only one now. We used to keep four or five, his daddy, Rascal, and some mares. When Rascal died, we sold the mares to save on feed. I don’t need them now, so it’s only him. Someday, I’m going to buy another mare and put him to stud, but he’s young, and there’s plenty of time for that.”

“He’s so good. How do you train a horse like that?”

“Like I said, I brushed and handled him from the day he was born. When he was a few months old, I started out by tying a loose rope around his middle. After he got used to that, I put a blanket under the rope. You can see he loves being brushed, so I would brush him and lean some weight on his back each time. When he was old enough, I put a saddle on him. When he got used to that, I put more of my weight on him until he was three years old. Then I got up on his back.”

“And he just let you ride him?”

George laughed. “No, he threw me off every day for three weeks. I’d leave the saddle on him for a few hours before I took it off, and I tried again the next day.”

“And he finally let you ride?”

“One day he threw me, and I landed flat on my back. It took all the wind out of me, and I had to lay there for a while until I could breathe again. He got all worried and came over and tried to get me up. He kept pushing at me with his nose and whuffing in my face. If it’s possible for a horse to get a guilty look, he had one. The next day he didn’t buck when I got on him. He stood stock-still. I finally got him to walk and then every day I took him out a little farther down the road. After a week or so, I got him to canter. He’s been good as gold ever since. He does anything I ask. A lot of saddle horses would never pull a wagon, but look at him. He’s just fine with it.”

Pawnee chewed on the long grass for a while and then acted as if he wanted to play. He came up behind George and bumped his nose against George’s back several times, harder each time, until George finally stood and paid him some attention. He took a brush out of his bag and brushed Pawnee’s long, bushy mane and the tail that almost reached the ground.

This inspired Lulu, and she found a bag of hair ribbons in her things and began sectioning off the mane and braiding it. She tied a different color ribbon to the end of each braids. Pawnee stood perfectly still, closing his eyes while she worked. When she finished, she patted him on the neck and said, “There, now you’re beautiful.” Pawnee turned his head, and that big powerful stallion nuzzled the girl with his nose and nickered to her. She wrapped her arms around his neck and hugged him.

George built a fire to keep the snakes and animals away, rolled out some blankets in a grassy spot, and we slept on the ground. The next morning, after we ate, George hitched Pawnee back to the wagon and drove it on the ferry. Blocks were put under the wheels to keep it from rolling around during the trip across the water. The driver seemed to know George right well. He pointed to Pawnee’s braids. “Got him all dressed up for church, George?” he laughed.

Lulu and I stood next to the wagon and held on the side rail, and Lulu held onto my waist with her other arm. George stood next to the driver, telling stories and making him laugh. The river pushed the ferry this way and that, and I held on so tight that after a while my hands went numb. The helmsman struggled to steer as best he could to get us across the river without going too far downstream. It seemed to me that we would never reach the other side, but we finally did. George drove the wagon onshore, and we waved goodbye.

George’s horse perked up his ears like it knew where it was going by then. We rode all morning and afternoon and only stopped once to let the horse eat a little while we finished up what was left in the picnic basket.

As night set in, Lulu fell asleep with her head in my lap and George and I leaned against one another and dozed off and on for the rest of the trip. I was jolted awake when the wagon came to a stop in front of a large, two-story house. Several dogs began barking. It was very early in the morning. There was no moon, and the sun hadn’t begun to rise. The sky was so dark it was hard to make out what the house looked like.

“Here we are, Maude,” George said, climbing down from the buggy. He walked around to my side and took the sound-asleep Lulu in his arms. I climbed down and followed George up the path to the front door.

As we reached the top step, the door opened, and a scowling old woman stood there in the glow of an oil lamp. She held out the light, and I could see she had a large dog on each side of her, baring its teeth and rattling a growl.

George took a deep breath. “Ma, this is my wife, Maude.” He nodded down at the sleeping Lulu, “and this is her daughter, Lulu.”

The old woman’s mouth fell open. She stepped right in front of me and stared hard at my face. She was almost as tall as I was, even with a bent back. Her stringy gray hair hung over her shoulders.

I almost cringed at how she glared at me. Then George’s mother turned her attention to Lulu. She looked down at my child asleep in George’s arms and reached out a hand. My motherly instinct made me take a step forward, but the old woman just ran a finger down Lulu’s cheek and smiled sweet as anything. “Put her in Bessie’s room,” she said.

She held the door open for George so he could carry Lulu inside, then slammed it shut. That left me standing on the porch with the two dogs, which still showed their teeth and growled even louder. It hurt my feelings and made me mad at the same time. I thought, “So, that’s how it’s going to be.”

I pushed the door open, stepped inside, and kicked it shut before the dogs had a chance to get in behind me. I followed George and his mother up the stairs. He carried Lulu in one of the bedrooms. His mother pulled the covers down on the bed, and he laid Lulu down.

“I’ll get the rest of the things out of the buggy and bed down Pawnee,” he said and left.

The old woman stood in the corner without saying anything. She watched as I took off Lulu’s shoes and socks and undressed her down to her underwear. I pulled the covers up, kissed her cheek, and turned around.

“I’ll show you George’s room,” the old woman said with a sharp voice.

She led me to the large corner bedroom, stepped aside for me to go in, and slammed the door shut as she left. She took the lamp with her. I stood there in gloom, barely able to make out the shapes of the furniture.

One window faced the back yard, and one was to the side. As my eyes got used to the dark, I looked around. There was a good-size bed against one wall, with a small table and lamp next to it, and a chest of drawers on the opposite wall. I looked around the table for matches to light the lamp, but here weren’t any. A chair sat by the window facing the back yard. There were no curtains. I walked to the window and looked out. I could see the outline of a few small buildings. One, I recognized as the outhouse. Another looked like the chicken coop, and one more towards the back of the property with a chimney that I figured was a smokehouse. A row of trees looked like an orchard.

In the light coming from the open door of the barn, I saw the dogs walking around and the shadow of George moving about. After a minute, he cam

e out carrying my cedar chest and brought it as far as the back porch, then returned to the barn, fetched the oil lamp, and headed for the house. The dogs followed his every step. He stopped to stroke some cats that gathered around his legs and rubbed against him. I watched as he made his way to the outhouse. I knew I would need to do that before I went to bed. After a few minutes, George came in the room with the lamp. He set it on the table and then went back to bring the chest. He said, “The wagon is in the barn. I’ll get the rest of your things tomorrow.”

I stammered. “I, ah, I need to--go before I go to bed.” I could feel myself blushing.

“Do you want to go to the outhouse? You can use the slop jar. It’s right under the bed there.”

I couldn’t bring myself to do that right there in front of him. “I think I want to go out.”

I picked up the lamp, went downstairs, and found my way to the kitchen and the back door. The dogs were lying on the porch. As soon as I stepped outside they ran up to me, heads lowered, ears back, and started snarling. My stomach turned over with fear. Then I was angry again. I was so worn out, I was ready to fall over, and I’d taken about as much as I could stand.

I glared at them, pulled back my lips, and showed my own teeth. “Sit yourselves down, and be quiet, or I’m going to kick you both ‘til you can’t walk.” The dogs sat right down and were quiet.

I made my way down the path singing and stomping my feet a little to run off any snakes. The dogs followed me and sat outside the door when I went in. The lighting was dim. I wasn’t pleased by what I smelled. What little I could see in the dark, it looked clean enough, but my family and the Connors had kept a fresh outhouse, moving it to a new spot from time to time, and dumping lime in the pit often enough to kill any odor. I thought, “I’ll have to talk to George about this in the morning.”

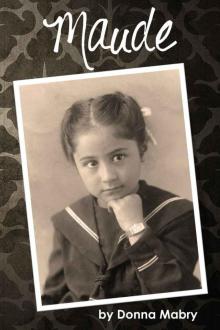

Maude

Maude